The complete story of my stay in Beijing is in the following part of this message.

You can have a look at the pictures by going to the messages between March 8th and March 18th.

Two Rare Wine Dinners Organized in Beijing With My Wines Paired With the Cuisine of Daniel Boulud

1 – origins of the project and departure

This writing tells the tale of an event which, I hope, will matter in my life: setting out to do wine dinners in China. So, let’s start like they do in the movies, with a flashback. One of my Balladur-era friends, that is, a friend I’ve had for thirty years, has several children, including a son who worked as a consultant for my company. As he works alongside me, he sees the bulletins coming out of the printer, and that gives him an intense desire to participate in the dinners I rhapsodize about. We readily agree on a trade: I will invite him to some of my dinners, and he will request events for the pleasure of his friends or clients. He works with an international consultancy, and so decides to invite associates from that important firm. The wives are to take part, which gives an amiable feel to the evening, for which Eric Fréchon has reserved for us alone the whole summer restaurant at the Bristol.

The event was clearly enjoyed by the consultants invited, because just a few months later, they asked me to hold a dinner in honor of one of their Chinese clients. Since I had never been to China, for me, the image of that country came directly out of Hergé’s comic books Tintin in Tibet and, especially, The Blue Lotus. That view of things was most likely pretty dated. How surprised I am, then, to discover a very tall man, probably about six foot three, all smiles, not yet forty, who has the easy manner of someone who has attended the most prestigious American universities! The dinner at the Grande Cascade goes marvelously well, as though we have been friends forever, and Desmond – for that is his name – asks me to organize two dinners for him in Beijing.

The gestation period for these events was particularly laborious. Before my departure, I sent and received hundreds of e-mail messages while working everything out – with the strange quirk that the response time to my messages was as long as if a marathon runner had carried each screed by hand. You cannot imagine how the logistics of a meal become ten times more complicated when no one gets back to you. Add to that a time difference of six or seven hours, and you can see how nothing goes smoothly.

Desmond is a great wine lover, and he buys his bottles most notably through a Hong Kong broker. As a precautionary measure, Desmond told the broker the wines I had suggested serving. Of course, as was to be expected, Desmond had created an adversary for me, one who naturally criticized my choices. Did he see me as a potential competitor? I don’t know. But between intelligent people, diverging opinions are quickly overcome.

Desmond asked me to call on the services of Daniel Boulud, one of the top New York chefs, who had just opened a Maison Boulud in Beijing. The idea was particularly appealing, and contact was established between Daniel Boulud, his Beijing chef Brian Reimer and me. I liked the extreme open-mindedness of the great chef, with whom conversations were immediately cooperative. After several hours of talks on the phone, it seemed we had some fine menus planned.

More than anything else, it was the lack of responses to my questions that was stressful to me. And, to make matters worse, my wife decided not to come with me to Beijing, deciding I should go it alone, though I had thought we would discover together the fascinating world of a culture far older than Europe’s.

Yet all the pieces of the puzzle slowly came together, and suddenly I found myself at Charles de Gaulle, leaving for Beijing. Entering the waiting area for first and business class passengers has a deliciously Ancien Régime aspect to it; you feel as though you’re part of a privileged caste. Everyone is smiling and attentive, and all your resolutions for dietary moderation instantly fall by the wayside. The buffet beckons, and a very pleasant glass of Deutz champagne is even better for being sipped in circumstances of unabashed elitism. Hangman, one last flute before I die!

But sinful temptation does not only arise from supposedly belonging to a certain class. In the plane, finding myself seated not next to my wife, but instead a forty-something gentleman used to transcontinental travel, a conversation got rolling and grew so animated that it would be hard to say which of us was the more chatty. For my neighbor was a wine enthusiast and had sold wine for part of his career. So, when he ordered a whisky, I ordered a whisky, and when he ordered wine, I ordered a beer, because no one should attempt the impossible: Air France’s wines are not my cup of tea. He ordered an Armagnac, and I ordered a cognac, thinking I would cure a budding cold through the wildest debauchery.

2 – the first day in Beijing

The plane crosses snowy, deserted regions. It arrives in Beijing under sunny skies. The luggage turns on the carrousel, and I would never have imagined there could be so much of it. The suspense of waiting for your luggage is almost unbearable, and I realize I am not made to deal with that kind of stress. A man who seems to be in charge announces that all of the suitcases have been unloaded. I start to worry. Someone asks me my name and tells me that it is on the list of lost luggage. How can it already be on the list? I learn that the suitcase never left Paris, which is why they were informed in Beijing. The man in charge of lost objects tells me that my suitcase will be delivered tomorrow. This is the one with all of my clothing in it.

The son of another childhood friend, a business consultant in Beijing, has sent me a chauffeur to drive me to the hotel, which is a nice touch, it seems to me. When I see the little sign with my name on it, I feel like railing against the fact that my suitcase has been lost, but the chauffeur only speaks Chinese. He drops me at my hotel, and when I go to the reception desk, I am told there is no reservation under my name. To prove the receptionist wrong, I have to open my laptop. And that is when it decides to open up to an error message, twice, which makes the tension behind the counter even greater. When the confirmation e-mail opens, the pretty young woman tells me that my hotel is in the next building over. I immediately think of my suitcase, because if it is brought to the wrong address, too, I’ll be spending the week wearing yellowing undergarments.

One building down, after going through the formalities, I finally enter my room. It is as hot as a sauna. I plug my computer into the hotel’s cable internet jack and discover that though I can receive my e-mail, I cannot respond to it. Several minutes later, my room looks like a train station the day before Christmas, because in it are: two computer repairmen working on my internet connection, a heating specialist who turns out to be as ineffectual as the computer repairmen, and a charming young woman who is apparently none too shy, because as I have called her to send the only linens in my possession to be cleaned, she feels no need to pretend she’s not looking when I give her the only articles of clothing I have on.

While I wait for my laundry back, I take a shower, as the plane trip has left me sorely in need of one. The shower head is as broad as a beach umbrella, which means it’s impossible to avoid the first cold drops. Through some quirk of fate, it takes five minutes for the water to start warming up, since the building clearly doesn’t have a hot-water circulator. This painfully long moment makes me reflect on the human condition. When the body is wet and one is getting ready to engage in the virile act of soaping up, it’s common to stop the water flow. The inventor of overly large shower heads should be drawn and quartered in some town square for having invented this diabolical torture device. Because once you turn off the water, the shower head distills drops that go “plop, plop” on your head. Now, my faithful readers may suspect that I have a fixation on showers, and that is not untrue. Because in hotels, you have as much space as the price range allows for, but the space allotted to the shower is ridiculously small, and the hardware, in order to seem “modern,” provides you with the opposite of comfort. That rare moment when you might think yourself the equal of Caruso or Pavarotti should be the object of intense attentiveness. But it seems to be handled more as a constraint than a luxury. How many times do we ask ourselves where to put our towel so that we can grab it without turning the place into a swimming pool?

My laundry comes back, but the girl has not had my undergarments cleaned (I am not making this up). So I go out to buy some t-shirts and underwear while I wait for my suitcase to arrive. Hotel reception sends a tall young bellhop with me to act as my guide. He is clever, because he has me buy what I need at discounts I would never have thought to ask for, and he makes me laugh, because he keeps trying to get me to believe that everything looks good on me. He ostentatiously memorizes the secret number on the back of my credit card, and pries into my wallet with both his eyes and hands.

Afterward, I return to the scene of my computer situation. The person claiming to be the hotel’s “computer engineer” has kindly deteriorated the functionality of my computer, which turn of events I greet with a remarkably Zen-like attitude. It is time to meet a Chinese woman who is a businessperson and very much down to business, accompanied by her two associates. Her companies work in high-tech, but she has also formed a sales group for rare wines via a number of cellars in Beijing and Shanghai. Our contact was arranged by a banker friend in Paris who works with Chinese concerns. This woman exudes a desire to win and comments on the global crisis with a high-handedness that is worlds away from the Parisian take on things, where everything seems to be caught in tiny internecine struggles. We look at what could create ties between my activities and hers. Thinking on a Chinese scale overturns all the usual ways of considering things.

Back up in my room, I see that the computer tinkering has taken a turn for the worse. The heater in my room, the computer setup and the hot water in the shower all clearly have my best interests at heart. Everyone is all smiles and really would like to fix things. But is good will enough? A young receptionist, who has come up to my room, given that it is now a large-scale operating theater, is working with me to help me choose the restaurant I will have dinner in. My choice is a Japanese restaurant, where my frugal repast is washed down with a dry bottle of beer.

When I come back up to my room, a mobile air-conditioning device is there, making the same noise prewar airliners used to, and like someone full of hot air, it churns out the same pointless temperature it sucks in.

Can this pile-up of problems be the harbinger of a happy stay? With that question in mind, I slip between the sheets.

If happiness should come, it won’t be this morning. It is so hot in my room that I decide with virile courage to declare to the reception desk, “Either you get me a cooler room, or I’m changing hotels.” They promise me another room and ask me to pack my suitcases. That is about the only time I’m vaguely pleased, since the larger of my two suitcases has not been delivered yet.

3 – scouting lunch at the Maison Boulud

It is nice out, so I walk to the Maison Boulud. There is nothing like it for drinking in the thousands of little details that give you a better feel for a city. Contrasts lie on every street corner. The Maison Boulud is situated on a square overlooked by five boxy buildings belonging to the American embassy. The Maison Boulud is within one of the five buildings – the ambassador’s residence. When I get there, there is a long red carpet before the door. It’s there for the Beijing Bank of China, which has just created a prestige credit card and is inaugurating it by reserving the entire place for its rich clients. Statuesque hostesses are handing out orchids, which seem like badges displaying the guests’ social standing. Notable guests are requested to write their signature on a large wall panel in the bank’s name. Young artists will perform between the speeches. I head to the bar, where a suitcase brand (clearly an allusion) is presenting its models. Elsewhere, pretty Chinese women are putting on makeup together, doubtless in preparation for the show. I am joined by the chef, Brian Reimer, who is American and cooks here under the guidance of Daniel Boulud. Young, dynamic and smiling, with very good French, Brian shows me that he has understood how my dinners work. Then the sommelier Koen Masschelein, a Belgian who has worked in great restaurants such as Les Crayères and the George V, comes up to me. Young and dynamic, too, he seems motivated to oversee the two dinners.

Since all the bustle is taking place on the ground floor, my table is set up upstairs in a pretty private room that is tastefully decorated, as is everything at the Maison Boulud, where the modernist style and the color scheme create a tonic, dynamic, powerful feel. This is when Ignace Lecleir, the restaurant’s manager, shows up; he, too, is tonic and smiling. My meal is meant to give me a feel for Daniel Boulud’s style and allow me to make potential comments on the dishes. I drink only water.

Pleasant, discreet waitresses offer me bread and set down a plate with five little hors d’oeuvres. The tastes are direct, clear, varied, joyous and reassuring. They have enough variety to match appealingly with champagne. The oyster in seaweed aspic with a bit of caviar is perfect. There is an iodine scent, and the oyster is very pure tasting. The dish is the ideal pairing for a great champagne.

The white tuna marinated with carrot and lime, replaced here by a similar fish, as the white tuna will only arrive tomorrow, is delicate and subtle, even if the lime is somewhat assertive. It will go well with champagne. This is extremely subtle cooking.

The scallop atop celeriac puree with diced celery and chicken jus plays on tastes that have a kind of refined charm. The scallop is fat and sweet and very natural, and the celery highlights its freshness. This is a very elegant dish. Balance and purity characterize this dish, which is minimalist and delicate like Chinese calligraphy. The squab with turnips is presented in two parts. The breast meat is cooked with precision, but it is not very expressive. The leg is served with forcemeat, wrapped in a sheet of brik pastry. The turnips are delicious. This will all go very well with a fine red wine.

The litchi dessert is delicious, but it is clearly too strong. The litchi is meant to go with SGN Riesling. It must be more of a suggestion, softer. This needs to be worked on with the chef, and absolutely served without sorbet.

Koen came often to ask me for comments. After a good coffee with very pleasant madeleines, I chose the glasses with Koen, and Ignace Lecleir showed me the possible places for the table as well as table shapes. As it is absolutely necessary for me to be able to talk to everyone at the table, I chose an ellipse shape that would lead to our being in a private room, rather than the restaurant’s main dining room.

I went down to the cellar to verify my wines. They were all in fine shape and did not seem to have been compromised by the trip from Paris to Beijing.

The rumor mill is already at work, and a Hong Kong wine auction house knows everything about what’s planned. A young agent from that concern accompanies me back to my hotel, first on foot because the surrounding streets are closed: today there is a Chinese communist party congress. For security reasons, there is an even greater military presence than usual.

I return to my hotel, where a new room with Himalayan temperatures awaits me; my missing suitcase arrives, as well. Tonight I am having dinner with Desmond. A smile – my own – at last shines on Beijing.

4 – Scouting dinner at the Maison Boulud

According to my plans, a dinner at the Maison Boulud would allow me to continue the process of understanding Daniel Boulud and Brian Reimer’s cuisine. Desmond became part of the plans when he announced he would have dinner with me there. Having him all to myself is a privilege I cannot refuse. When I arrive twenty minutes early, Desmond is already at the bar, deep in conversation with Daniel Boulud. We shake hands, the chef and I, because we have never met before, though we have spent two hours talking on the phone deciding on the menus for the two dinners. We start chatting. Daniel describes the Paulée wine event in New York, for which he and other chefs such as Michel Troisgros have prepared food for four hundred people; the event is unique in its orgy of great wines. We mention the two dinners, the first of which is for the official members of the Chinese government, as well as several important entrepreneurs, and the second will include several participants from the first dinner, this time with their wives. Desmond does not want press coverage, in order to respect the participants’ privacy. Desmond and I raise a glass of Perrier-Jouët Rosé, which is refreshing but leaves one unmoved. Daniel leaves us to head off to the kitchen, despite the jet lag.

We sit down to eat in the pretty dining room with its impressively high ceiling and modern, colorful decoration. To accompany the varied meal, I suggest a 1998 vintage champagne from Egly-Ouriet, a special bottling whose name I forget. The champagne is delicious, with a smoky, expressive taste, and will work well with all of the dishes we eat. Examining the dishes while talking with Desmond, who is fascinating to talk to, is not the same thing as at lunch, because one isn’t paying as much attention. But I do notice that the meal is completely different. At lunch, all the dishes were about finesse and subtlety. This evening, they are more virile and self-affirmed. Is that because Daniel Boulud has shown up? I would have thought as much, but Daniel came over at the end of the evening and told us that he had been busy with a dinner for one hundred guests upstairs and had not prepared our dishes. Obviously a chef has to look out for his own interests.

The hors d’oeuvres were a little less striking than the ones at lunch. Soup will never be a good match for wine, because it dries out the palate. A foie gras-based composition led me to tell Brian Reimer that the confited onions were justified if he were making the dish for himself. But because our interest is also in pairing dishes with wine, they are really to be avoided, because the balance should be with the wine and not the sour insistence of the onions.

The red tuna steak is delicious, but the bacon wrapped around it is too smoky. That has to be softened. The squab is perfect. But the most magical meat is that of the suckling pig, which has been cooked for fifteen hours at low temperature. It is divine. But, once again, it’s important to do away with the sour vegetables that counterbalance the velvety fat of its flesh, if the balance can be struck naturally through the wine itself. The desserts are technically perfect, but once again, we should be looking for tastes more than desserts, which I explain to the smiling Brian Reimer, who has the intelligence to listen carefully.

While we eat, Desmond talks about fascinating things. With the INSEAD business school in Fontainebleau, where he studied (I should have filmed the hand gestures and quizzical looks needed until I finally understood he was talking about Fontainebleau and the INSEAD, because the pronunciation of those two names in English by a Chinese person is exotic), Desmond participated in an on-site study, with 25 graduates of that school, in the slums of Bombay. A woman who makes fabric at home earns four dollars a month. At the same time, a rich Indian can build a palace that will cost a billion dollars. That is shocking to Desmond, who is, moreover, very committed to business operations for charity. In the same vein, in a slum of one million inhabitants, he believes that a third of the people don’t have any form of identification and therefore could die without anyone knowing what happened to them. So we talk about demographics, a subject I have been obsessed with for over thirty years and which I discover is shared by my Chinese friend, who is only forty years old. We talk about the evolution of the respective powers in China and India, and the evolution of the world. Sounding our analyses off each other is extremely enriching.

Desmond is funny, because he tries to fill up my calendar like you’d fill a duffle bag: by stuffing it. If I added everything he wants me to do, twenty-four hours a day would not be enough. Desmond picks up the check in the restaurant, which is an elegant gesture. He takes me back to my hotel. Tomorrow, I will visit the Great Wall of China and the Forbidden City. Before going to sleep, I read the China Daily, which gives a rich view of the way of thinking about politics and the economy in this, the largest country in the world.

I fall asleep eager to know more about a new world that will perhaps, soon, experience a great epic story.

5 – The Great Wall of China and the Forbidden City

The next morning at 10 o’clock, I ask the hotel’s concierge if my guide has arrived. He shows me a pretty Chinese woman of about thirty years old with very long hair – I will never find out if it is a wig or her natural hair – and, for a fleeting moment, I wonder if she won’t guide her way into my heart. Alas, she is chaperoned by a chauffeur, which instantly puts an end to my reverie. We set out for the Mutianyu section of the Great Wall of China. I am bothered by the tenaciously lingering odor of stale tobacco that fills the car. Rebecca, the guide, explains many symbols to me during the trip. The value of numbers; why the Imperial City is square; the calligraphy of the word “China,” with a point for jade, a synonym for imperial fertility; the meaning of the “empire of the middle”; the use of yin and yang in architecture; the importance of dragons and phoenixes, etc. Her explanations are fascinating, and I am then put to the test with the mercantile side, because obviously, tourism is supposed to bring in money. We enter a factory that makes vases which I learn are made in a style called “cloisonné.” Interconnected pieces of copper are affixed to the vase and colors are incrusted in them. It looks like enamel. The polite thing to do would be to buy one of the multicolored vases, but I’m not in the mood for it.

We reach the foot of the Great Wall and take an open chairlift (on separate chairs) to reach the top. I hoof my way along several hundred yards of this gigantically constructed wall and come back down on a kind of bobsled on a stainless steel track. I have no immediate plans to participate in the Winter Olympics, but I made good time, given the equipment available.

The imperishable souvenir vendors are glued to me in their great desire to sell something. We come back into town to visit the Imperial City. A teeming crowd fills the space, and I note that 95% of them are Chinese. Rebecca explains the importance visiting this place has for the Chinese. I should say that I have never been as impressed by such a visit. It is so colossal yet so palpably refined that I am in a constant state of wonder. Each second, I find myself thinking that this visit alone would have justified my trip. Fascinated, I delve into every hidden cranny and scrutinize each architectural or sculptural detail, giving thanks to human ingeniousness and feigning to overlook what cruelty and human dramas this splendor doubtlessly hid.

The visit was an intense moment in my life.

The hotel I am staying in has the piquant advantage of including a sizeable helping of everything I hate. There is always the devoted employee who, right when you have honey running down the sleeve of your pajamas, comes to ask you if you have socks that need washing. There is always another employee who, right when you’re stumbling as you pull on a pants leg, asks you if he can stock the mini-bar for you. There is the kindly cleaning lady who makes up your room but forgets to replace the towels. There is the zealous concierge who calls to inform you that the taxi you asked for is there, but when you get downstairs to the lobby tells you it’s no longer there, because it couldn’t wait. And there is also your trusty shower head, which distills hot and cold unpredictably, just to surprise you. My morning was therefore spent cursing human ingenuity, which excludes excellence. A pleasant interlude then takes place in the hotel lobby. I am waiting for my room to be cleaned, and I am brought a message saying that someone whose name I don’t recognize would like to come say hello to me. The person is an Austrian who lives in New York and who will take part in the two upcoming dinners. He introduces himself and we talk about wine. I can feel his enthusiasm for this evening’s experience. I find it motivating. I then eat a modest sandwich in my room for lunch, interrupted by attempts at good service that I find truly irritating. At 2pm, a taxi takes me to the Maison Boulud.

6 – opening the wines for the 113th wine dinner

I go down to open them in the cellar, because it doesn’t seem like a good idea to bring them upstairs into the dining room only to bring them back down. But the smell of french fries and fried onions that fills the area worries me a little. I show Koen how I officiate, and opening the bottles does not pose any serious problems. The scents of the 1961 La Tâche and 1989 Henri Jayer Cros Parantoux are fairly closed, while the 1996 Coche-Dury Corton-Charlemagne is like a foghorn. It is an explosion of aromatics. My two 1845 Cyprus wines are the absolute expression of my grail. I am fairly satisfied. With Koen, the sommelier, I bring the red wines up from the cellar to the private room we are using. The other wines are chilled. I run into Daniel Boulud and suggest infusing a little black pepper into the madeleines, because the Cyprus wines have a powerful scent of that spice. Daniel will brilliantly follow my wish.

I correct the spelling or presentation mistakes on the menus that have been printed by the restaurant, and it’s time for a short nap at my hotel.

7 – 113th wine dinner at the Maison Boulud in Beijing

Twenty minutes before the hour in question, I enter the large red- and black-decorated room the Maison Boulud has reserved for us. The table is oval, as Ignace Lecleir had opportunely suggested, and Desmond is already deep in conversation with important figures from the Chinese or Beijing regional governments. There were supposed to be twelve of us, which is the maximum acceptable number for my dinners, then we were down to eleven, as of yesterday; in fact, there will be ten of us, with one participant arriving extremely late. The thirteen wines planned for twelve have become profuse for ten. Stiff upper lip, gentlemen! Here, I say “gentlemen,” but there is also one woman among us, an important personage, as she is the head of managing spaces and heritage sites for the city of Beijing. There is a Frenchman, who was the link between Desmond and me; an Austrian who lives in New York; Desmond; and six other Chinese men, of whom only two speak English. I am forced to avail myself of Desmond’s services, as well as those of the charming woman, to make myself understood. Unlike the day before, when Li Wei multiplied the length of my sentences tenfold when translating them into Chinese, Desmond divides them by the same factor. When I make a comment that seems indisputably urgent, I am unable to say whether I have been translated or not.

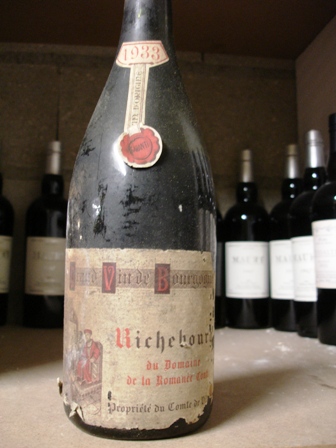

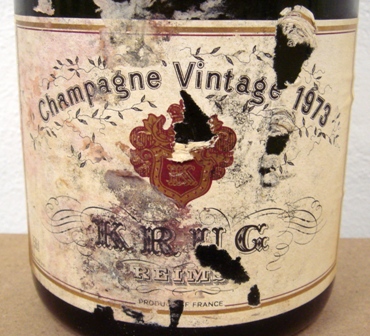

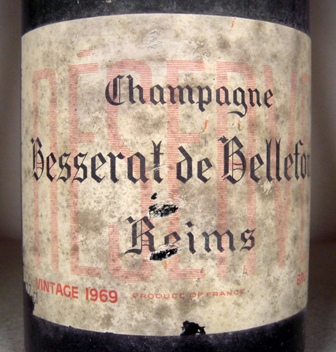

As I assemble everyone to explain how we go about things to get the most from the dinner, I realize that my remarks are meeting with true interest. The mood is ebullient, happy, yet studious. The ensuing dinner will demonstrate for me that my “rules” have been applied and followed, notably when I asked them to drink slowly. Before sitting down, we start to drink a 1973 vintage Krug Champagne from magnum. Its color has canted toward a delicate orange-ish pink. Its bubbles are very weak, but there is still some fizz to it. This champagne allows me to define the notion of “ancient wines,” which my guests find very interesting.

The menu, composed by Daniel Boulud and brilliantly executed by Brian Reimer, has been fine-tuned over the course of multiple communications, which was a great pleasure for me. Here it is: hors d’oeuvres / white tuna marinated with carrot and lime / spiny lobster with saffron, mussel cream and cauliflower custard / cod with porcini mushrooms and celeriac / veal shank braised with sage, velvety potatoes / truffled filet mignon of pork, stewed root vegetables / duck roasted with plums and stuffed new turnips / seared slice of foie gras / young Stilton and caramelized mango / warm licorice madeleines.

We sit down to eat, and the Krug accompanies the four little hors d’oeuvres. It is only later that I realize that the Pata Negra ham I requested as a fifth starter has not been served. I explain my sensations about these starters in order to measure how far they evoke something for my interlocutors. The potato stuffed with caviar gives the champagne, in my opinion, much more verticality. The blintz with salmon, on the other hand, which is a much more comfortable match, develops its horizontality. The crab with basil combines the two by adding great balance to the champagne, rounding it out. And the fourth starter, a scallop dish, is a much less significant addition to the taste of the champagne. I get the feeling that Desmond is somewhat dubious at the start of my explanations, then little by little, he seems to digest them and communicate their interest to his guests. This is also a chance to help them understand that at this dinner, we are not only trying to understand the wines, but also to get a feel for the pairings planned between the food and the wines. During this time, the Krug opens up in our glasses. Our Austrian friend is a great lover of old champagne and communicates his enthusiasm to the whole table.

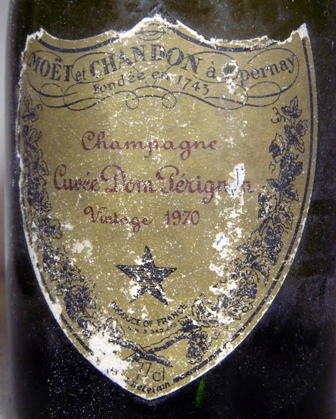

The 1959 Salon Mesnil-sur-Oger Champagne is incomparably perfect. This is certainly the greatest 1959, an extremely rare vintage, that I have drunk from that august house. The previous one had come directly from the cellars at Salon and was dead. This one is absolute perfection. Everyone understands that the 1973 Krug is an old champagne, whereas this 1959 Salon, which is nonetheless fourteen years older, is a young champagne. It has all of its bubbles, it has the yellow color of a young champagne. It unfurls completely and doesn’t show any signs of its age. The acidity is mastered, and its length is immense. The pleasure it gives is total. I wonder if I have ever drunk a better champagne. I don’t know, but I know that it is among the most gorgeous ones I have ever tasted. The dish, wonderfully simplified by Brian Reimer, with the exquisite flesh of the white tuna and the lime spurring the Salon on, creates a match that is absolutely exact. This will happen again.

The 1988 Bouchard Père & Fils Chevalier-Montrachet is the most beautiful possible example of the relevance of my way of opening wines. The same wine opened just before serving could never have the opulence, the balance, and the accomplishment this shows. The wine is joyous, multifaceted, complex, and it delights us.

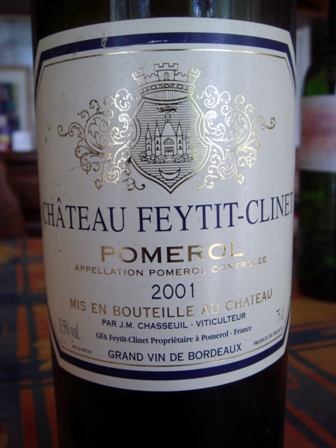

I am served first on the 1961 Château L’Angélus Pomerol, and the first nose is fairly dusty, but one senses the wine will open up. I observe those around me, and their interest in this wine is clear. The wine opens in the glass and becomes a very subtle Pomerol. The dish is wonderful, and the pairing with the cod, which is one of the combinations I love, is absolutely divine.

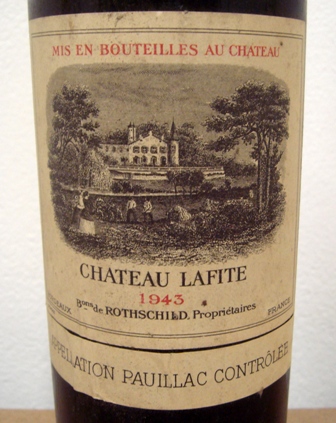

I had brought to Beijing two bottles of 1943 Château Lafite-Rothschild Pauillac, and in case neither one of them worked out, I had brought a 1964 Lafite, whose strength I am well acquainted with. Given the uncertainty over the bottles, I opened the 1943 with the lower fill, since it seemed logical that a potential rescue could come in the form of the bottle with the higher fill rather than the other way around. The smell of the wine was so persuasive on opening, which Koen also confirmed, that I decided we would drink this bottle. What characterizes this wine is its subtlety and softness. It is the very definition of velvety. Everything about it is refined, and the pairing with the veal shank astounding.

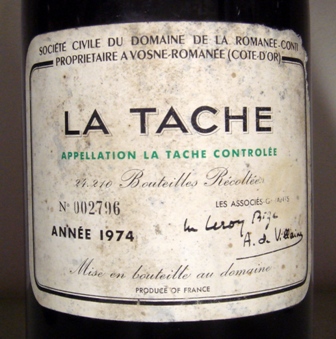

The 1961 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti La Tâche has a somewhat alcoholic nose to it, and its taste is one-of-a-kind. Even if I do get rapturous about it, I will say that it is unreal in its perfection. It is complicated and complex and kaleidoscopic. When the Beijing officials went with Desmond to visit Daniel Boulud’s kitchens before the meal, I had time to whisper to Brian that the La Tâche smelled so much of truffles that he should go heavy on them when serving the dish, which is what he did. The La Tâche is imperiously full of truffle aromas, but, to my great joy, Desmond also finds notes of roses, a subtle scent that is the stamp of wines from the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. I am amused to notice that with the truffled filet mignon of pork, the La Tâche becomes a truffle. Its saline bitterness is divine. Its finish is a thing of greatness. I realize that with all the superlatives these wines deserve tonight, choosing the best one will be quite difficult.

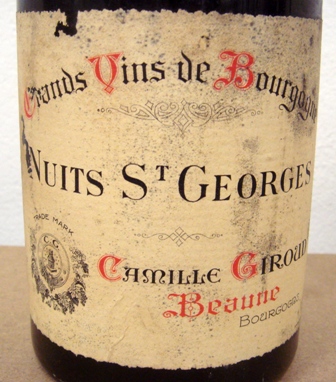

With the same dish, we also drink the 1928 Camille Giroud Nuits-Saint-Georges. It is very soft, very pleasant, and it holds its own next to the La Tâche, despite a clear difference of station. Several guests point out how much the 1928 evolves in the glass, becoming even more charming. And, curiously, the 1989 that will follow sets the 1928 off even more brightly when we come back to it.

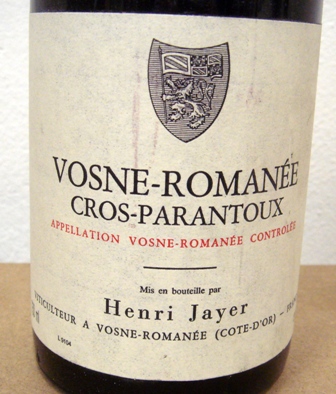

The 1989 Henri Jayer Vosne-Romanée Cros Parantoux certainly represents the perfection a wine from the Côte de Nuits can have among the twenty years surrounding the 1989 vintage. It is kind enough to improve the 1928, and yet it remains less charming than the 1961 La Tâche. In the end, the 1989 is a perfect wine, whereas the 1961 is a rabble-rouser, a timeless wine that stands apart.

I had decided during the preparations for the meals, which took several months, to serve the 1996 J.-F. Coche-Dury Corton-Charlemagne at this point in the dinner, so that its force would not kill the wines that came after it. As the ones after it were sweet wines, there was no risk of that happening. When I had discussed with Daniel Boulud the possible dishes at this point in the meal, I had suggested seared foie gras. The quality of Chinese foie gras is absolutely exceptional. The smoky fleshiness of the liver is astounding. The pairing is so grandiosely wonderful that I ask Koen to have Daniel Boulud come taste it at our table, since a place has been freed by the early departure of one of the Chinese guests. Daniel sits down and says to Desmond, “I have already held one hundred exceptional dinners. But I think I have never met anyone as exacting for details as François.” I took this remark as a friendly compliment. The match between the Coche-Dury and the foie gras is incredible. The slightly sugary note to the foie gives the Corton-Charlemagne extraordinary ripeness and expressiveness. Such an astonishing pairing should be memorized and set down in the annals of the UNESCO.

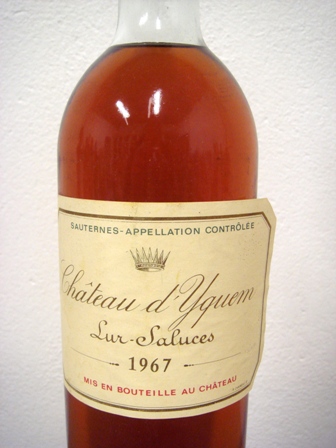

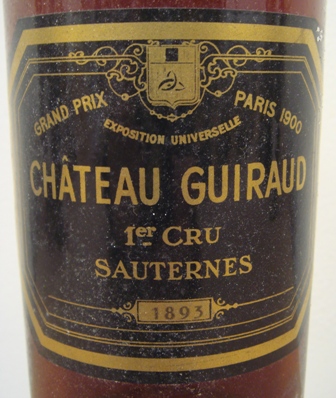

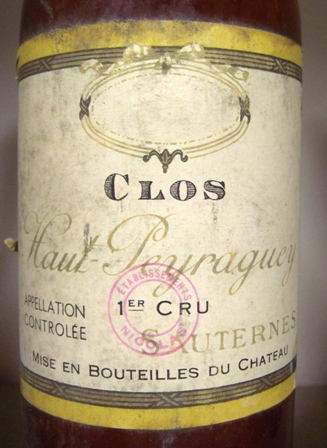

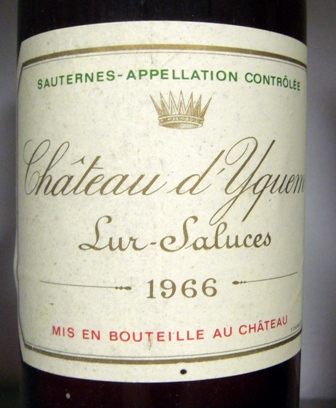

Now we taste two wines together, the 1967 Château d’Yquem and the 1893 Château Guiraud Sauternes. The latter wine was reconditioned in its original bottle in 2000. It is, moreover, the only reconditioned wine at this dinner. With the Stilton, the Guiraud is a more pleasing match. I teach the Chinese how to chew the Stilton and sip the Sauternes so that the combination works better. They graciously play along and happily note that the way one manages the quantities is not unimportant. The Yquem is a greater Sauternes than the Guiard, especially in the 1967 vintage, which is a masterful year, but the 1893 is has more forceful charm in its tea aromas and its subtlety. It is an extremely refined wine, whereas the Yquem still has the brash power of youth.

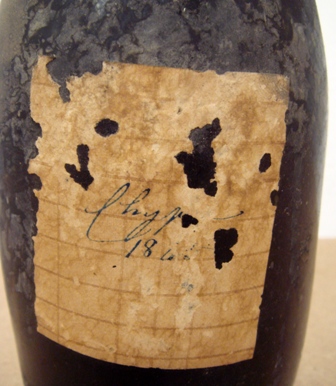

Now we approach the two Cyprus wines, the 1845 Cyprus Commandaria Ferré and the 1845 Cyprus Commandaria, wines whose different origins I am unable to define. The bottles have different shapes and their tastes are fairly close, even if the one that is not “Ferré” seems even subtler to me. Everyone knows that these wines are the pinnacle of what I love. I had asked for madeleines with a suggestion of licorice and, earlier in the afternoon, a pinch of black pepper. The two Cyprus wines do have black pepper to them, but this time it’s candied orange that dominates, rather than licorice, in the non-Ferré, which I prefer, while the Ferré doesn’t have candied orange, but rather licorice. These wines are a thing of utter refinement.

At the start of the meal, I asked Desmond if he would allow us to vote for our favorite wines, and he responded, “Of course.”While voting is particularly tough amid so many superb wines, which did not suffer from the journey they made a month and a half ago, I see that my fellow diners are intelligent in their voting.

Let’s look, first, at the wines that did not garner any votes from the nine people voting: the magnum of 1973 Krug, no less; the 1988 Chevalier-Montrachet; and the 1943 Lafite. So the nine others (I count the Cyprus wines as one) obviously had to have been brilliant if such fine wines had no votes.

The 1959 Salon garnered four first-place votes. The 1961 La Tâche obtained three first-place votes. The 1961 Angélus and the 1893 Guiraud each had one first-place vote.

The consensus was therefore the following: 1 – 1959 Champagne Salon Mesnil-sur-Oger, 2 – 1961 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti La Tâche, 3 – 1893 Château Guiraud Sauternes, 4 – 1961 Château L’Angélus Pomerol.

My vote is: 1 – 1959 Champagne Salon Mesnil-sur-Oger, 2 – 1961 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti La Tâche, 3 – 1845 Cyprus Commandaria, 4 – 1989 Henri Jayer Vosne-Romanée Cros Parantoux.

The most extraordinary pairing was the 1996 Corton-Charlemagne with the seared foie gras, and then certainly the white tuna with the 1959 Salon, even if many of the dishes could claim second place. I must salute the creative efforts of Daniel Boulud, whose recipes were reworked and streamlined to match the wines. This was remarkable. Koen did great work as a sommelier.

While many people, including most recently the rich Chinese businesswoman, had warned me about the slim chances of getting the Chinese to understand my dinners, I must say that I was impressed by the opposite – that is, their desire to understand, their wise reactions, and the way they followed the rules of my dinners. So it was with a weary yet joyous heart that I left the Maison Boulud, telling myself that I had just realized the fairly incredible project of ushering wines from my world into the cultural universe of some very nice Chinese people. The language barrier did not prevent us from sharing true emotions.

With a congratulatory e-mail, Desmond confirmed the next morning that all of his friends had been delighted. The 113th wine dinner on Chinese soil with French cooking was a great success.

8 – an unexpected encounter

Thanks to my brother, some ten years ago I met an architect who works on major projects and has lent his name to brilliant creations in France and acted as a consultant in China for very important operations. He consults for cities with populations greater than that of the Paris region, and I remember that when he came with his wife to our house in the south of France a few years back, he was just finishing up the project for a great Chinese theater. We had been trying to find a time to meet up, but our schedules had been hopeless at finding a common date. Before leaving for China, I had reached out to him and asked if he might by chance be in China when I planned to. The window of opportunity was one night, tonight, and Denis joins me with his assistant, Li Wei. I am so tired from walking everywhere in the cold today that I ask them to have dinner with me at my hotel, though they had reserved a table in town. We choose a restaurant that serves both Chinese and Italian food. At first you would think that they would have made some efforts to decorate, but the place is in fact sinister, cold, and repellent. But that is unimportant, because our reunion is too precious a thing to let that get in the way.

I talk about my upcoming dinners in Beijing, showing him the menus, and Denis racks his brain to see if one of his Chinese friends could be interested. Li Wei is the one who suggests a name. Denis tells her, “Call him.” She asks for a little guidance in leaving the message, then calls the rich friend. By some extraordinary stroke of luck, the friend is just then leaving the Opera, and his chauffeur is a few hundred feet from our hotel. She has hardly had time to end the call when a smiling couple of about forty comes in and sits down at our table. The conversation is held in Chinese, so Denis and I start the conversation and Li Wei translates. I am fascinated to see that what I say in a dozen words suddenly takes on the length of the multi-volume Oxford English Dictionary. Li Wei talks, talks, talks, and talks some more. She later explains to me that she made the most of each translation to add some stories about what we had talked about before they’d gotten there. The Chinese friend, who is soon to inaugurate a great museum, of which he is the owner and initiator, asks many questions in order to understand the world of ancient wines, which is totally unknown to him. We talk at length, and the conversation ends with an invitation for me to visit his museum, which will not yet be open during my stay. I will go with Li Wei, whom our interlocutor seems to like.

Thus I discover that friendship is important in China, as Denis seems to be a good friend to this Chinese man and his wife. Though they were heading home, they went out of their way to stop by our hotel, accepted that we talk to them about the unknown activities of a stranger, and they plan to see the stranger again, through Denis’s intermediacy. All of this shows an open-mindedness I find remarkable. This country surprises me in a good way.

When Denis and I are saying goodbye as we’re parting ways, we both say, almost simultaneously, “If we want to see each other again, let’s make a date in China!”

9 – the French restaurant at my hotel

The day after the meal at the Maison Boulud was reserved for recovering from the fatigue and stress of it all, since it had taken over four months to organize the dinner. I no longer know if I am suffering from jetlag, because I sleep at times that have nothing to do with either the French or Chinese time zones, and the same goes for my periods of wakefulness. I force myself to write about all of the events thus far, because if I don’t do it now, the second dinner in Beijing will erase the memory of the prior event.

The Raffles Hotel has several restaurants. I have tried the Japanese one, where you eat soberly in a timeless atmosphere that naturally doesn’t lead to waywardness. The half-Chinese, half-Italian restaurant was pretty sinister, as it completely lacked ambiance. I still had yet to try the French restaurant Jaan, whose chef I had run into by chance in the elevator. Young and smiling, he inspired confidence. In a large dining room with colonnades, a bar and a piano lounge are set off to the left. Behind drapes between the columns on the right is a French restaurant. The reception is amiable and the ambiance is really the most pleasant of the three restaurants. I hear French being spoken at many of the tables. The young chef’s cuisine explores Oriental tastes, and it is a very interesting experiment. Alas, if you’re served a cod fillet that is not quite cooked through and has bones in it, your enthusiasm tends to flag. Of course, that could just have been a stroke of bad luck, since it seems clear that I seem to attract small imperfections, like an old sardine attracting the cats in the neighborhood.

10 – Peking duck lunch

Desmond has booked my schedule in a very authoritarian way, but he doesn’t follow up with any of the activities I had thought he would guide me through. I am thankful for what must have been a misunderstanding on my part, because I really do need some rest. He had, however, scheduled a lunch for the two of us, on Saturday at Da Dong Roast Duck, which, according to him, is the greatest duck restaurant in Beijing. The day before, I receive an e-mail from Maggie, his secretary, informing me that Desmond will be unable to honor our appointment and asking me if I will accept to have lunch with her there, instead. The answer is yes, and so at the scheduled time, I reach the restaurant.

When I give my name, no one understands me. And as in all the comic routines about that subject, when at last they understand what my name is, they pronounce it exactly as I had been. At least, that’s what I think. This restaurant, with its humble appearance, serves a spectacular number of covers. The Tour d’Argent with its famous duck dish must not serve one twentieth the number this restaurant does. The waiters who cut up the roasted fowl are possessed of fascinating dexterity, with an operational style in which each gesture has a precise meaning and use. Maggie is thirty-five, though to me, she looks ten years younger than that. She smiles a lot, and we chat amiably while enjoying copious, spicy food. We start with duck foie gras, which I find a little bland in taste and dry, and the following dish, which requires a fire extinguisher, is frankly unpleasant to me, because I find myself biting into strange things. I put on my glasses, and when I discover that these are the scaly feet of ducks cut into thin strips, I refuse to touch the dish again. What follows is far more pleasant, as the duck meat is truly delicious and cooked to perfection.

11 – concert at the new Beijing Opera House

Desmond has had a ticket sent to me for a concert by the Berlin symphony orchestra at the National Centre for the Performing Arts in Beijing. This opera house, designed by a French architect, has been open for two years. Clearly, the taxi driver who takes me there mustn’t know it very well, because he drops me off about a mile from the entrance. As gigantic moats surround what is in effect an enormous bubble of mercury of Brobdingnagian dimensions, I am almost late in getting inside. A huge crowd has thronged to this concert, and I note that probably about 95% are Chinese. Not far from my seat, Desmond is surrounded by several friends, including the woman who attended the dinner at the Maison Boulud.

The evening’s program is exclusively written in Chinese, so I find myself faced with this concert exactly as though it were a blind wine tasting: “I know this piece by heart, but which is it?” The conductor Ingo Metzmacher has orchestrated remarkable interpretations of very well-known pieces from the classic German repertoire, and I discover just how remarkable the acoustics are in the concert hall. Several points seem absolutely remarkable to me: this immense opera house was packed to the gills with Chinese people who had come to hear European music. How much success would an opera playing Chinese music meet with in France? The audience members around me were clearly eager to learn something. Families came with small children. Not one was poorly behaved. Everyone applauded at the right time, without breaking forth at an inappropriate juncture, and applause and calls for encores took place as they should in polite society. It was a fine lesson in good behavior. When I left the hall with Desmond’s friends, one of them asked me, “Aren’t you disappointed in this country for being so behind the times?” I told him that it was quite the contrary, that my impression was quite positive.

Coming back to my hotel from the opera house, I saw crowds of extremely young people. The number of girls between the ages of 15 and 25 is extremely high, and in the groups of young people, there are often twice as many girls as boys. When the girls grow up to be mothers, the population in China will witness quite an awakening.

Along a surrounding wall, there are benches. And on the benches, couples hug and kiss. Further on, a young man is taking a picture of his date, using the indirect lighting of a lamp that lights the wall. This is all so fresh and new. Small military groups parade here and there with a choppy forced step. Taking their picture is prohibited. They are young, baby-faced. Even at night, people take pictures of the immense portrait of Mao Tse Tung, though the streetlamps have gone dark.

This city is spectacularly teeming with life and activity. Knowing that people applauded Beethoven and demanded three encores, in order to honor the conductor, gives one another view of China. Is it the right one? I don’t know, but it is possible. There are many things in this country that are pleasant surprises for me.

12 – opening the wines for the 114th dinner

To get to the Maison Boulud to open the bottles, I decide to take major roads and cross Tiananmen Square. On the streets and in the square there is a huge crowd for a Sunday afternoon; transposed to Paris, it would be a dream for any union leader. A compact army seems to occupy the space, with great calm, camaraderie and curiosity.

Pulling the cork of each bottle usually requires two steps. First, with a classic sommelier corkscrew, I raise the cork a few millimeters – two or three. Then I take that tool out and use the long screw of

La très jolie décoration intérieure de la maison Boulud, et la table dressée avant le repas

Vingt minutes avant l’heure dite, je pénètre dans la grande salle décorée de rouge et de noir de la Maison Boulud qui nous est affectée. La table est ovale, comme Ignace Lecleir m’avait opportunément proposé et Desmond est déjà en grande conversation avec des personnages importants de l’Etat chinois ou de la région pékinoise. Nous devions être douze, ce qui est la limite haute acceptable pour mes dîners, nous devions ensuite être onze annoncés hier, mais nous serons en fait dix dont un arrivera fort tard. Les treize vins prévus pour douze deviennent pléthoriques pour dix. Courage messieurs. Je dis messieurs mais nous compterons aussi une femme, personnage important puisqu’elle est responsable de la gestion d’espaces et de patrimoines de la ville de Pékin. Il y a un français, qui fut le trait d’union entre Desmond et moi, un autrichien qui vit à New York, Desmond, et six autres chinois dont deux seulement parlent anglais. Je suis obligé de recourir aux services de Desmond, mais aussi de la charmante femme pour me faire comprendre. Contrairement à la veille, où Li Wei multipliait en chinois la longueur de mes phrases par un facteur dix, Desmond les divise par un facteur de même ampleur. Lorsque je fais un commentaire dont l’urgence me parait incontournable, suis-je traduit ou non, l’histoire ne le dira pas.

Au moment où je rassemble tout le monde pour donner les consignes pour profiter au mieux du dîner, je me rends compte que mes propos rencontrent un intérêt certain. L’humeur est joyeuse, rieuse, mais studieuse. La suite du dîner me montrera que mes « consignes » sont appliquées et suivies, notamment lorsque j’ai demandé de boire lentement. Nous commençons à boire debout le Champagne Krug magnum Vintage 1973. Sa couleur tend vers un rose orangé délicat, sa bulle est très faible mais le pétillant est intact. Ce champagne me permet de définir la notion de vin ancien qui intéresse beaucoup mes hôtes.

Le menu composé par Daniel Boulud et exécuté brillamment par Brian Reimer a été mis au point au cours de multiples échanges, ce qui est un immense plaisir pour moi. Le voici : Hors d’Œuvre / Thon Blanc mariné à la carotte et citron vert / Langouste au safran, Crème de moules et Royale de choux fleur / Cabillaud aux cèpes et céleri rave / Jarret de Veau braisé à la sauge, Pommes mousseline / Filet Mignon Truffé, Racines en Pot au Feu / Canard Roti aux prunes et Jeunes navets farcis / Tranche de foie Gras poêlé au naturel / Jeune Stilton et Mangue Caramélisée / Madeleines Tièdes à la Réglisse.

Nous passons à table et le Krug accompagne les quatre petites pièces de hors d’œuvre. Ce n’est que plus tard que je me rendrai compte que le Pata Negra que j’avais demandé comme cinquième morceau d’ouverture n’a pas été servi. J’explique mes sensations sur ces entrées pour mesurer si elles évoquent quelque chose pour mes interlocuteurs. La pomme de terre fourrée au caviar donne à mon avis une plus grande verticalité au champagne. Le blini au saumon au contraire, beaucoup plus confortable, développe son horizontalité. Le crabe au basilic fait la synthèse des deux en contribuant à un équilibre fort du champagne qu’il arrondit. Et la quatrième entrée à base de coquille Saint-Jacques représente un apport moins significatif au goût du champagne. Je sens Desmond dubitatif au début de mes explications puis petit à petit, il semble qu’il les intègre et en communique l’intérêt à ses invités. C’est surtout l’occasion de faire comprendre que dans ce dîner il ne s’agit pas seulement de comprendre les vins mais aussi de s’imprégner des accords prévus entre les mets et les vins. Pendant ce temps le Krug s’épanouit dans nos verres. L’ami autrichien est un grand amoureux des champagnes anciens et communique son enthousiasme à toute la table.

Le Champagne Salon Mesnil sur Oger 1959 est incomparablement parfait. C’est certainement le plus grand 1959, année rarissime, que j’aie bu de cette grande maison. Le dernier avant celui-ci provenait directement des caves de la maison Salon et était mort. Celui-ci est d’une perfection absolue. Tout le monde comprend que le Krug 1973 est un champagne ancien alors que ce Salon 1959, pourtant plus vieux de quatorze ans est un jeune champagne. Il a toute sa bulle, il a la couleur d’un jaune de jeune champagne. Il se développe complètement et n’a pas le moindre signe d’âge. L’acidité est contrôlée, la longueur est immense. Le plaisir est total. Je me demande si j’ai déjà bu un meilleur champagne. Je ne sais pas, mais je sais qu’il entre dans le groupe des plus beaux que j’aie jamais bus. Le plat, merveilleusement simplifié par Brian Reimer, avec la chair exquise du thon blanc et le citron vert qui aiguillonne le Salon, crée un accord d’une exactitude absolue. Cela se reproduira encore.

Le Chevalier Montrachet Bouchard Père & Fils 1988 constitue le plus bel exemple possible de la pertinence de ma méthode d’ouverture des vins. Car jamais le même vin ouvert juste au moment de servir ne pourrait avoir cette opulence, cet équilibre et cet accomplissement. Le vin est joyeux, multiforme, complexe et nous réjouit.

Je suis servi en premier du Château l'Angélus Pomerol 1961 et le premier nez est assez poussiéreux, mais on sent que le vin va s’épanouir. J’observe autour de moi et l’intérêt envers ce vin est évident. Le vin s’étend dans le verre et devient un Pomerol très subtil. Le plat est merveilleux et l’accord avec le cabillaud, qui fait partie des combinaisons que j’adore est absolument divin.

J’avais apporté à Pékin deux bouteilles de Château Lafite-Rothschild Pauillac 1943 et au cas où aucune des deux ne conviendrait, j’avais apporté Lafite 1964 dont je connais la solidité. Compte-tenu de l’incertitude, j’avais ouvert la plus basse des deux 1943, puisqu’il paraît logique qu’un secours éventuel vienne de la plus haute que de la plus basse. L’odeur était tellement convaincante à l’ouverture, confirmée par Koen, que j’avais décidé que nous boirions celle-ci. Ce qui caractérise ce vin, c’est la subtilité et la douceur. Il est la définition même du velouté. Tout en lui est finesse et l’accord avec le jarret de veau est prodigieux.

La Tâche Domaine de la Romanée Conti 1961 a un nez où l’alcool se fait sentir, et son goût est unique. Même si je dithyrambe, je dirai qu’il est fantastique de perfection. Il est compliqué et complexe et kaléidoscopique. Lorsqu’avant le repas les officiels de Pékin ont visité avec Desmond les cuisines de Daniel Boulud, j’ai eu le temps de glisser à Brian que La Tâche sent tellement la truffe qu’il faudrait qu’il ait le bras lourd au moment de servir le plat, ce qu’il fit. La Tâche est impérieusement dotée de parfums de truffe mais, à ma grande joie, Desmond lui découvre aussi des notes de roses, parfum subtil qui signe si bien les vins du Domaine de la Romanée Conti. Je m’amuse à constater qu’avec le filet mignon truffé, La Tâche devient truffe. Son âpreté saline est divine. Son final est de première grandeur. Je me dis qu’avec tous ces superlatifs mérités par les vins de ce soir, le vote sera bien difficile.

Sur le même plat, nous buvons aussi le Nuits-Saint-Georges Camille Giroud 1928. Il est très doux, très agréable et il tient sa place à côté de La Tâche, malgré une évidente différence de noblesse. Plusieurs convives feront remarquer à quel point le 1928 évolue dans le verre pour devenir de plus en plus charmeur. Et chose curieuse, le 1989 qui va suivre le met encore plus en valeur lorsqu’on revient vers lui.

Le Vosne Romanée Cros Parantoux Henri Jayer 1989 représente certainement la perfection que peut avoir un vin des Côtes de Nuits sur les vingt ans qui encadrent 1989. Il a la gentillesse d’améliorer le 1928, et il reste malgré tout moins charmeur que La Tâche 1961. Il faut dire que le 1989 est un vin parfait, alors le 1961 est un vin canaille, hors du temps et hors des modes.

J’avais décidé lors de la préparation du repas qui a pris plusieurs mois de mettre le Corton Charlemagne J.F. Coche-Dury 1996 à ce moment du dîner, pour que sa puissance ne tue pas les vins qui le suivent. Comme les vins à venir sont des liquoreux, le risque n’existe pas. Lorsque nous avons discuté avec Daniel Boulud des plats possibles à ce stade, j’ai suggéré un foie gras poêlé. La qualité du foie gras chinois est absolument exceptionnelle. Le fumé et le charnu du foie sont confondants. Et l’accord est si grandiose que je demande à Koen que Daniel Boulud vienne le déguster à notre table puisqu’une place s’est libérée, du fait du départ anticipé de l’un des convives chinois. Daniel s’assied et dit à Desmond : « j’ai déjà fait des centaines de dîners d’exception. Mais je crois n’avoir jamais rencontré quelqu’un d’aussi exigeant sur les détails que François ». J’ai pris cette remarque comme un compliment amical. L’accord du Coche-Dury avec le foie gras est incroyable. Le léger sucré du foie donne au Corton-Charlemagne une maturité et une expression extraordinaire. Il faudrait pouvoir mémoriser un tel accord pour le figer dans les annales de l’UNESCO.

Nous goûtons maintenant deux vins ensemble, le Château d'Yquem 1967 et le Château Guiraud Sauternes 1893. Ce deuxième vin a été reconditionné dans sa bouteille d’origine en 2000. C’est d’ailleurs le seul vin reconditionné de ce dîner. Sur le stilton, c’est le Guiraud qui est le plus agréable. J’apprends aux chinois comment mâcher le stilton et boire le sauternes pour que la combinaison se fasse mieux. Ils se prêtent à ce jeu de bonne grâce et constatent avec plaisir que la façon de gérer les quantités ajoute de la pertinence. L’Yquem est un plus grand sauternes que le Guiraud, surtout s’il s’agit du 1967, année magistrale, mais le 1893 est d’un charme plus percutant dans des arômes de thé et dans sa subtilité. C’est un vin extrêmement raffiné, alors que l’Yquem a encore la fougue et la puissance de la jeunesse.

Nous abordons maintenant les deux vins de Chypre, le Chypre Commandaria Ferré 1845 et le Chypre Commandaria 1845, vins dont je serais incapable de définir les différences d’origine. Les bouteilles ont des formes distinctes et les goûts sont assez proches, même si celui qui n’est pas « Ferré » me paraît encore un peu plus subtil. On sait que ces vins correspondent à l’apex de mes amours. J’avais demandé des madeleines avec une suggestion de goût de réglisse et, en ce début d’après-midi, des traces de poivre noir. Les deux Chypre ont bien le poivre noir, mais cette fois-ci c’est l’orange confite qui domine, plus que la réglisse, chez le non Ferré que je préfère, alors que le Ferré n’a pas d’orange confite mais de la réglisse. Ces vins sont dans des registres de raffinement total.

Au début du repas, j’avais demandé à Desmond s’il acceptait que nous votions et il m’avait répondu : « bien sûr ». Alors que voter est particulièrement difficile devant l’abondance de vins superbes, qui n’ont pas souffert le moins du monde du voyage qu’ils ont fait il y a un mois et demie, je m’aperçois que mes convives ont une belle intelligence de votes.

Regardons un instant les vins qui n’ont pas eu de votes des neuf votants : le magnum de Krug 1973, excusez du peu, le Chevalier-Montrachet 1988, et le Lafite 1943. Il faut donc que les neuf autres (je compte les Chypre pour un) aient été brillants pour que de si beaux vins n’aient pas de votes.

Le Salon 1959 a obtenu quatre votes de premier. La Tâche 1961 a obtenu trois votes de premier. L’Angélus 1961 et le Guiraud 1893 ont obtenu chacun un vote de premier.

Le vote du consensus serait le suivant : 1 - Champagne Salon Mesnil sur Oger 1959, 2 - La Tâche Domaine de la Romanée Conti 1961, 3 - Château Guiraud Sauternes 1893, 4 - Château l'Angélus Pomerol 1961.

Mon vote est : 1 - Champagne Salon Mesnil sur Oger 1959, 2 - La Tâche Domaine de la Romanée Conti 1961, 3 - Chypre Commandaria 1845, 4 - Vosne Romanée Cros Parantoux Henri Jayer 1989.

L’accord le plus extraordinaire est celui du Corton-Charlemagne 1996 avec le foie gras poêlé et sans doute ensuite le thon blanc avec le Salon 1959, même si beaucoup plats pourraient revendiquer la deuxième place. Il convient de saluer l’effort de création de Daniel Boulud dont les recettes ont été travaillées et épurées pour aller dans le sens des vins. Ce fut remarquable. Koen a fait un grand travail de sommellerie.

Alors que beaucoup de personnes, dont encore tout récemment cette riche femme entrepreneur chinoise, m’avaient mis en garde sur la capacité d’apprécier le concept de mes dîners par des chinois, je dois dire que j’ai été impressionné par le contraire, à savoir leur volonté de connaître, leur sagesse de réactions, et leur adhésion aux règles de fonctionnement de ces dîners. C’est donc le cœur fatigué mais joyeux que j’ai quitté la Maison Boulud en me disant que je venais de réaliser un projet assez incroyable de faire entrer les vins de ma planète dans l’univers culturel de chinois très sympathiques. L’obstacle de la langue n’a pas empêché le partage des émotions.

Par un mail de félicitation Desmond me confirme ce lendemain matin que tous ses amis ont été ravis. Ce 113ème dîner de wine-dinners en terre chinoise sur une cuisine française fut un grand succès.

Daniel Boulud venu manger le foie gras, Desmond et son ami autrichien

La table en fin de repas

sur la nappe en toile cirée de la cuisine, nous avons fait un accord de troc entre une de mes bouteilles de Chypre 1845 et une bouteille de vin de paille de 1893 de Bouvret.

sur la nappe en toile cirée de la cuisine, nous avons fait un accord de troc entre une de mes bouteilles de Chypre 1845 et une bouteille de vin de paille de 1893 de Bouvret.

deux vues de la cave de Michel Chasseuil. Le plafond qui joue le rôle d’un miroir, grandit encore l’impression imposante de la cave

deux vues de la cave de Michel Chasseuil. Le plafond qui joue le rôle d’un miroir, grandit encore l’impression imposante de la cave

D’après ce que j’ai compris, il existe une dame Cathelin qui a peint avec ce pinceau et ce tube de peinture la célèbre étiquette du nom moins célèbre vin : la Cuvée Cathelin Ermitage de Chave

D’après ce que j’ai compris, il existe une dame Cathelin qui a peint avec ce pinceau et ce tube de peinture la célèbre étiquette du nom moins célèbre vin : la Cuvée Cathelin Ermitage de Chave

Lacrima Christi vin de Massandra 1897 du Prince Golitzin

Lacrima Christi vin de Massandra 1897 du Prince Golitzin

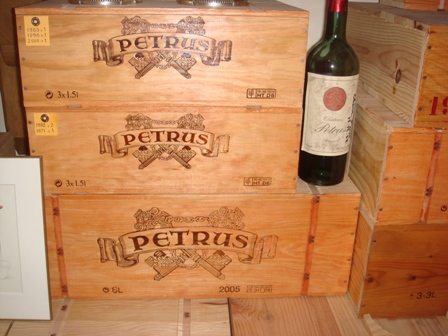

avoir des magnums de

avoir des magnums de  des magnums de Pétrus 2005, impériale de 2005, magnums de 1990, là aussi des rêves de collectionneur de vin !

des magnums de Pétrus 2005, impériale de 2005, magnums de 1990, là aussi des rêves de collectionneur de vin !

Pétrus des années mythiques sur des doubles magnums de 2005 et 2000. Je ne dois pas avoir la bonne retraite (dit avec beaucoup de jalousie)

Pétrus des années mythiques sur des doubles magnums de 2005 et 2000. Je ne dois pas avoir la bonne retraite (dit avec beaucoup de jalousie)

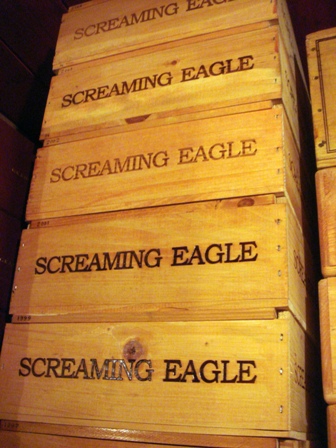

Obtenir des Screaming Eagle ne peut se faire que si l’on est reconnu comme acheteur sérieux. C’est le cas de Michel Chasseuil

Obtenir des Screaming Eagle ne peut se faire que si l’on est reconnu comme acheteur sérieux. C’est le cas de Michel Chasseuil

Une Yquem 1821 (j’ai redressé la photo, car elle repose couchée)

Une Yquem 1821 (j’ai redressé la photo, car elle repose couchée)

J’ai pris cette photo car j’ai aussi des bouteilles qui ont la même gravure dans le verre en écusson. Il s’agit de Louis Philippe d’Orléans. Je n’ai pas osé demander à quoi correspond ce « 350 € » ?

J’ai pris cette photo car j’ai aussi des bouteilles qui ont la même gravure dans le verre en écusson. Il s’agit de Louis Philippe d’Orléans. Je n’ai pas osé demander à quoi correspond ce « 350 € » ?

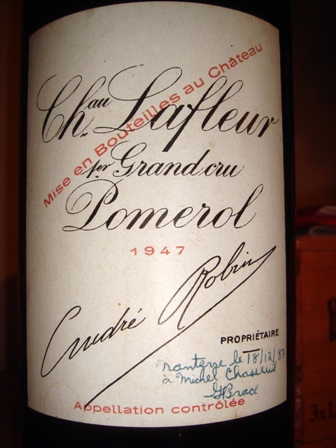

Il fallait bien finir ce petit reportage sur une bouteille qui a été bue, car c’est la vocation de toute cave, vocation à laquelle – j’espère – Michel reviendra un jour (?). Il s’agit d’un mythe, d’un rêve : Lafleur 1947 en magnum

Il fallait bien finir ce petit reportage sur une bouteille qui a été bue, car c’est la vocation de toute cave, vocation à laquelle – j’espère – Michel reviendra un jour (?). Il s’agit d’un mythe, d’un rêve : Lafleur 1947 en magnum

Cette cave mérite le respect, car il y a des flacons qui représentent le rêve ultime, le rêve inaccessible de tout amoureux du vin. Bravo Michel Chasseuil d’avoir acquis avec opiniatreté et tenacité ces flacons introuvables ou inaccessibles.

Cette cave mérite le respect, car il y a des flacons qui représentent le rêve ultime, le rêve inaccessible de tout amoureux du vin. Bravo Michel Chasseuil d’avoir acquis avec opiniatreté et tenacité ces flacons introuvables ou inaccessibles.